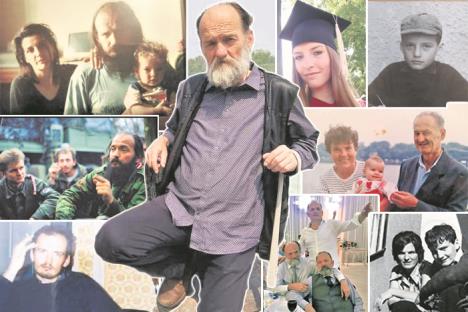

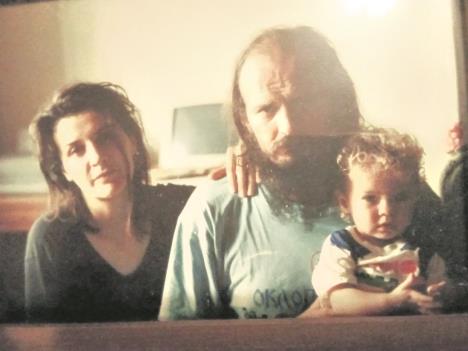

I KNEW BOSNIA WAR WOULD START, I TURNED 40 IN AN AMBUSH IN KOSOVO: The Life Story of Nebojša Jevrić, War Correspondent and Writer

My life story

He is said to be the best Serbian war correspondent, and one of the few who was welcomed on both sides, in war and peace. He visited and wrote about Kosovo, Kninska Krajina, Slavonia... He worked for the famous magazine Duga, and knew everyone from Giška to Arkan, Mladić, and Karadžić. He has read thousands of books and has written dozens himself. The reason for this conversation is his new release, Mrtvi dim (Dead Smoke), published by the Serbian Literary Cooperative

We descend from the priest Mirčeta Popović of Kuči. Prince Danilo ravaged Kuči. They cut off children's heads and carried them to Cetinje. They threw the bodies into the flames. "They burned with a green flame," wrote Marko Miljanov. Four of his sons fled to the Lim Valley. Isolated among the Vasojevići, they had to retreat to the mountains again and founded the village of Tmušiće. What a beautiful name. Now the village is deserted. Only dead smoke remains. Not a single hearth.

My mother contracted bone tuberculosis at the age of four. The German doctor said the leg needed to be amputated. My grandfather refused, and they took her to the village. What good is a girl without a leg, he thought. She lay immobile for six years. Then in the seventh year, a soldier from the medical corps passed by and said, "This child would walk if the bone protruding from the wound were removed." When no one was at home, my mother took a knife and removed the bone from the wound herself. She started walking. My grandfather ordered her to tend the sheep, but she refused. My grandfather was the absolute master and called the family his slaves. How could anyone refuse him anything? He beat her for three days with a wet rope, and on the fourth day, he agreed that she could go to school. She walked across Pešter to Sjenica on foot, then took a truck to Novi Pazar to attend a teacher training school. She kept the bone in her apron. When she graduated, she threw the bone into the Lim.

My grandfather, Novo Jevrić, used to beat my grandmother Ikonija and the children with his hat when they angered him. Our father was the same. He would endlessly tell us, his three sons, various fairy tales, stories, legends, and folklore. When he asked me to repeat the story, I always had a new and better ending. He would repeat the folk story "All is good, but a trade’s a trade" endlessly. When our mother got angry because of our mischief, he would say, "You won’t turn me against my sons."

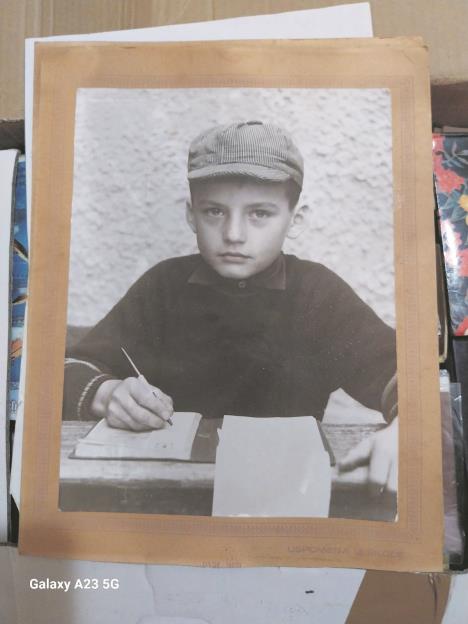

Childhood

I used to bring home destitute boys, my friends from the street. Some were killed, some became killers, and Karson jumped from the fourth floor of a building. "How do you always find those who take the wrong path?" my mother would scold me.

Every day, I brought home two books from the library. When my father turned off the light, I would read under the blanket with a flashlight. "You’re only chasing the plot," he would get angry. "Running after stories down the wrong path" became my life’s fate. When I was in eighth grade, my father enrolled in Russian Literature at the University of Sarajevo because of me. By the fourth year of high school, I read everything that was on his syllabus—from Dobrolyubov to Bulgakov.

First Love

Her name was Svetlana. I dedicated my first and last poem, Stamena, to her. Blagoje Baković and I organized very well-attended literary evenings in high school. But Svetlana got involved with our literature teacher, who was also a poet and a party secretary. A scandal erupted, and she had to move to Podgorica. But half of the high school learned my poem by heart. Some still recite it today, even though I never published it.

Instead of a graduation trip, they took us to the barracks on Banjica. To a rally. I was so angry that I bad-mouthed Tito. The authorities found out and expelled me from the rally. I spent fifteen days on the streets of Belgrade. And I fell in love with the city of freedom.

Entering Literature

Miodrag Bulatović was the most-read writer in Yugoslavia. I approached him on the street and told him I wanted to be a writer. I asked him if he would take me on as an apprentice. He took me to lunch and said, "Eat, who knows when you’ll be able to eat again if you want to be a writer." He liked my stories from The Black Suitcase, and when the book was published, he stated in Politika: "A poetic creation of devastating power." By the age of twenty, I had also published a novel, Adam’s Head.

Ivo Andrić's Coat

Most of my generation hadn’t even written their first poem. I distributed a thousand copies of The Black Suitcase to the girls at the Faculty of Philology and the Faculty of Philosophy. Soon, I became a famous writer on Knez Mihailova Street. Bulatović gave me the keys to his apartment and Ivo Andrić's coat. Andrić had told Bulatović, "Good things should go around. Give this coat to someone who will need it one day." When I tried to thank him, Bulatović said, "You don’t need to thank me. Pass it on to someone who needs help more than I do." I wore the coat for years, and then I gave it to Željko Pržulj, a warrior and writer from Nedžarići.

Besides Bulatović, I got to know many writers. I knew Desanka, Ćopić, Bora Pekić, Dragoslav Mihailović, Dedijer, Ćosić, Komnenić, Đogo, Bećković, Kapor, Bora Čorba, and they all came to the Writers’ Club. I learned something from each of them. I learned the most about writing from our best living stylist, Žarko Zolotić, who hasn’t published anything in years. Aleksandar Jerkov, a postmodernism moderator, and Ljubiša Jeremić, a critic of realistic prose, harshly criticized my books. It was something different that didn’t fit anywhere. It crushed me as a young writer.

The Society of Poets

I was accepted as one of their own by BAJKAN. The Society of Poets from the Bermuda Triangle (Brana Petrović, Ambro Marošević, Jaša Grobarov, Krsmanović, Aca Sekulić Nenadić), poets who used to sit in Lipa, Šumatovac, and Grmeč and drink. The best storytellers are those alcoholics who don’t have enough money for drinks, so they tell stories like Scheherazade in the hope that the one paying will stay seated longer. It was alongside them that I began drinking heavily. Above my head swirled the dead smoke.

The station brothel

I found a flat in Zagrebačka Street, across from the so-called “Pussy Park”. The old man Zosima tells Alyosha Karamazov as he sends him away from the monastery: "Go among the people." I met dealers, thieves, beggars, tramps, prostitutes, fake photographers, sellers of fake gold, shell game hustlers, and Džej. Waiters who would put crushed benzodiazepine in the coffee of weary travellers in Drvar, and then, when they fell asleep at the table, the thieves would clean them out of luggage and wallets. The dregs of Belgrade. People with hair growing between their fingers, who could turn into rats.

Arrested and Imprisoned

A writer is the lawyer for the most unfortunate before God. If you want to please God, you must step on the devil’s tail. I slept with them in the summer under the Sava Bridge. I constantly cursed the communists and bad-mouthed Comrade Tito. For this, I was arrested and imprisoned several times. In prison, I contracted tuberculosis. I sold banned books: Aliya's Islamic Declaration, Ćosić's Acceptance Speech, Gojko Đogo's Woollen Times, The Protocols, and writings by Ljuba Tadić, among others. I kept photocopies at an old outhouse keeper’s. She was an illiterate, ageing prostitute.

The Room at Mrs. Kajsija's

I wrote a ton of stories about the station. The novel Tihi rat (Silent War), and two films were made based on my station stories: Ružina osveta (Ruža’s Revenge) by Aleš Kurt and Šangarepo, ti ne rasteš lepo (Carrot, You Don’t Grow Well) by Boban Skerlić. Knez Mihailova, Terazije, Terazijski Greben is the most significant Serbian ridge. Forget Lovćen, Durmitor, Dinara. I didn’t reach Terazijski Greben via Balkanska Street but via Kamenička, first staying with Aca Sekulić, then at Beli Grad and Zlatna Moruna, where Apis used to sit with his conspirators. I found a room with Mrs. Kajsija Majkić in Knez Mihajlova Street. I met coyotes from Terazijski Greben, of whom only Dule Varićak is still alive, and has become a writer. I spent all day loitering at Kolarac, chatting up the ladies.

Three Phone Numbers and Two Slaps

I arrived from sexually backward regions and had to make up for it. One day, I managed to get three phone numbers and two slaps. Lonely passers-by. Street pick-up. That’s now forbidden by law. I was the first guest at Kolarac. I carried several copies of my first book Crni kofer (The Black Suitcase). I always carried a few copies with me in a cloth bag, where there was also room for half a kilo of brandy that we drank on the sly. And because of that, we were constantly at war with the waiters.

Winter in Knez Mihajlova Street

The first snowflakes were falling on the asphalt in Knez Mihajlova Street. Winter was coming, and we hated winter. Early December, 1981. My shoes had cracked, and we stuffed them with newspapers when it rained. I sat by the door, looking out onto the street, waiting to see who would appear first. Sleep-deprived office workers who were late for work passed by. She appeared in a fur coat and a fur hat. She wasn’t in a hurry. She stood in front of the shop window and looked. I was looking at her. I was cold and didn’t feel like going outside. I had just enough money for one round.

"Madam, miss, even though you’re a military officer, would you have a drink with an artist at liberty?" I knelt before her and looked at her pleadingly. I helped her with her coat and hat. She was wearing a Chanel suit and smelled of "Opium," which was in vogue at the time. I was in a knitted wool jumper that my mother had knitted. I smelled of sweat, of sleepless nights.

A Magical Dedication

She sat with me. I gave her a book. "I’ve been walking along Knez Mihajlova for three months since my husband, a captain, went to sea. And no one has invited me for a drink. That’s why I came in with him. No one has tried to pick me up." "Why do you drink that rubbish?" "That’s what we drank last night, too."

"The best drink for a hangover is champagne!" She ordered cheese and champagne. Waiter Rade was flustered. Manager Mića’s ears were fluttering with excitement: "Of course we have it. This is a reputable café!" They weren’t allowed to accept dollars—it was the communist era, and they didn’t accept credit cards—so she paid by cheque. I spent a long time writing the dedication: To Laura, this book with the hope that she will read it better than it was written. From Nebojša Jevrić, Knez Mihailova 35, attic. Drop by! On the last page, I wrote her a poem by Sinan Tatarin, Sinan Gudžević, a poet from Golija, "Thank You": "Thanks to all those great women, who without a word lay down with me, who, with their silent consent, saved me from all kinds of humiliation and lies!"

Laura Arrives

She put the book in her bag. She ordered drinks for the café staff. Rade, who earned his first tip from our table, bowed deeply. The snow had stopped falling. She left just as she had arrived. Drunk, with champagne bubbles popping in my brain, I went to the Student Club of the Faculty of Philology and continued drinking brandy from a teacup. In the morning, the postman woke me up. "A telegram for you."

What telegram? I thought something had happened to someone back home. The telegram, which I still keep among my old manuscripts in the basement, read:

"I’m coming tonight. Laura."

Cheese in a Pudding Dish

I started tidying up, but it was a mission impossible. The landlady, Mrs. Kajsija, looked at me in disbelief when I asked for a vacuum cleaner and a duster. "I’ll also need, if you can lend me, some pudding dishes and a mixing bowl." Then I went to the shop and bought a kilo of flour, yeast, and a litre of unboiled milk in a bag. I learned while hiking in Bjelasica, staying in mountain lodges, how to knead bread and make cheese.

I didn’t drain the freshly made cheese of whey; instead, I poured it into the pudding dishes. It was the best remedy for my already strained liver, so Granny Ikonija had packed me a starter and rennet so I could make it myself. By six o’clock, everything was ready. Laura arrived at seven. She was a child of Dedinje and had never tasted homemade bread or fresh cheese. "Cheese pudding..." she said. "I read the book last night. And the poem at the end of the book. Just so you know, I believe in you."

And then she pulled out an unopened set of silk sheets from her bag and made the bed. She undressed slowly. Underneath her Chanel suit, she was wearing suspenders and stockings. It was a night worth a lifetime. The next day, the captain returned from the ship. I never saw her again.

Convenience Store

The old tactic of lunatics from Knez Mihailova Street—they pretend to be in a hurry, but they’re actually going nowhere. Then my brothers started studying, and I could no longer afford to pay for the flat. Plus, my bed was broken by my godfather Bato Mašković while he was fooling around with some sculptress from Dinara. Bulatović began avoiding me; he couldn’t stand drunks. And I discovered the convenience store, the only shop in Nušićeva Passage that was open all night. I moved in with Saša the Convenience Store, where all those who had nowhere else to go spent the night. Years passed, and I didn’t write anything.

Entering Journalism

When I begged Bulatović to help me find a job, he said it was like trying to find a job for Grobarov. He even called my father to take me to rehab for alcohol. Back then, there was a café called Mandarina in Čumićevo Sokače, before it became a shopping centre, which didn’t bring in its tables and chairs at night. At one table sat a team of journalists from Zum Reporter, and at another table, I sat with my group. I spent the whole night talking about events at the station. Before dawn, Ivan Miladinović invited me to come to the Reporter office. I wrote six pages of stories about prostitutes, dealers of fake gold, and so on. A week later, it was published, and I entered journalism. They only published six issues before Reporter folded. Half of the editorial team and I moved to Duga, and the rest is history in journalism and literature.

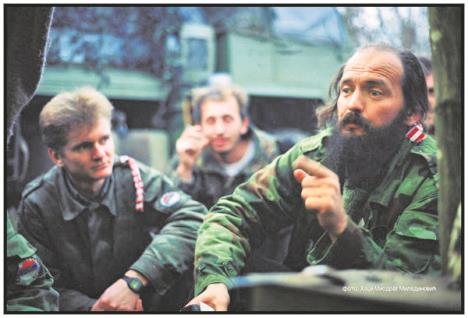

Another War Began

I knew the war would start. In the summer of 1990, while covering Jovan Rašković’s election campaign with fifty writers, ten painters, and the Patriarchate Choir, I visited every village in Krajina. In each one, I found supporters. When it started, I crossed the Danube by ferry and reached Slavonia. Arkan was still in prison. I arrived in Tenja. There, I photographed my first dead body.

He was about to throw a grenade when a burst of gunfire cut him down. He had blue eyes. There was no one to close them. He held an activated grenade in his hand. On the other hand, he wore a safety pin ring. His fingers were clenched around the pin, and as his body decomposed, there was a danger it would activate. Flies buzzed out of his open mouth. One landed on my forehead as I bent down to photograph him. For years, every time I saw a fly, I thought it was that one. I stayed for a month. I couldn’t contact anyone.

Like in Babel’s Story

My report from Tenja was read across the country. I became famous without even knowing it or benefiting from it. When Giška was killed, I went to Gospić. We escaped from Gospić to Medak and forgot four of our men. Dugi Lainović, naive as a French maid, sent me with three others to cover the street so they could cross. We cut the wire with scissors from a rifle and descended to the road, 300 meters from our positions. Rade Šiptar handed me two crates of ammunition for the Browning and ran towards the forest. I went to pick up the crates, and then I heard a "click." I stood frozen in the field. "Run, scribbler."

In vain. Then an anti-aircraft bullet hit the tree next to me and split it in two. I dropped the crates and ran. Like Ben Johnson. I broke all records. I wandered through the Lika plateau and only reached Medak in the dark. The night before, we had all slept in the gym on mats. In the dark, just before midnight, I entered and collapsed on the first available bed. In the morning, I asked for a light from the person lying next to me. He was dead. Next to him lay another dead man. The rest of the mats were empty. They had been killed during an attack from Bilaj and Ribnik. I felt like I was in one of Babel’s stories.

Serbian Roulette

"What is Serbian roulette?" asked the RAI journalist. "Uno, due, tre... Even Russians didn’t invent it; the Serbs did. In the last chapter of A Hero of Our Time by Lermontov, 'The Fatalist,' it’s played by Lieutenant Vulic, a Serb. You take grenades and climb onto a rock. On one, two, three, you pull the pins. You mustn’t press the spoon. The money is under the rock. Whoever throws the last grenade gets the cash."

"Did you play it?"

"I want to bet on you, writer-fighter."

"Sure, Roberto."

At midnight, there were five of us on the rock. Beneath the rock were worthless inflationary dinars and Roberto’s dollars. Roberto was trembling. A yellow rose of urine appeared on his white trousers. Naturally, I threw first. The last man counted to five, and the grenade exploded in the air. Gunfire erupted along the entire front line.

A Hero Travels to The Hague on a Donkey

Roy Gutman spent all night in Pale buying drinks. He was waiting for dawn for us to get drunk so he could ask, "Who raped the most Muslim women?" "Gruban, everyone knows that."

Don Gruban is the hero of Miodrag Bulatović’s novel, who ran a brothel during the Second World War and sent the proceeds to the partisans. He had such a strong vein that they had to tie it in a knot. The book was translated into twenty languages. It’s like accusing Don Quixote in Spain. We promised him a photograph. He promised everything..

In the morning, we headed to Neđarići, where journalists don’t usually go. When the warrant was issued for Radovan and Ratko, Gruban was also on it. "War criminals indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia." Warrants for their arrest are held by their respective capitals. Photos not available for the following: Gruban. DOB: unknown. Nationality: unknown. Description: unknown. Address: unknown. Neđarići, Sarajevo.

Four Years in Sarajevo

People only went to Neđarići as a punishment. I went there and stayed. There is only one street connecting Neđarići to Ilidža: Kasindolska, the street of death. Our territory was only six hundred meters wide. They fired from Igman, they fired from Stup, snipers shot from the student dormitories. Kasindolska was the lifeline. If they cut it off, they wouldn't need the tunnel under the airport. No one counted the number of attacks..

Out of one hundred and fifty defenders, one hundred and twenty-five were killed. When people mention Košare, they should also mention Kasindolska. In Ilijaš, out of five thousand people, three thousand were killed. The Turks were in the hills above. After Dayton, the population of Ilijaš scattered all over the world. Ilijaš is not mentioned in history textbooks. Neither is the Jewish cemetery. Nor Slavko Aleksić. Nor the Ozren Mountains. I spent four years in Sarajevo. I celebrated Serbian New Year alone on Grbavica, listening to the radio. I had arrived in Sarajevo when a wedding guest was killed.

Kosovo

On the 17th of May, 1999, I turned forty in an ambush near Slatina Airport, close to Priština. I stole a bottle of Mostar "Žilavka" from 1965 from my sister Darinka Jevrić—a keepsake from some old love of hers. She refused to leave Priština. "Is my head more valuable than the head of some nun from Devič?" she said to me, the great Serbian poet. In the dark, I spent the whole night telling people who I was, what I did, and where I had come from. I had come from Islam Grčki, from the home of Vladan Desnica. Ten years earlier. In the morning, I set out for Peć to see my uncle Miloš, who had hands like Kiro Radović—big, strong, gnarled. He was healthy and a hard worker. He drove me to Dečani, where I wanted to confess. But the monk with big, warm blue eyes whom I had chosen had other duties.

Later, Miloš was kidnapped by the Albanians and sold for spare parts. I walked barefoot from Dečani to the Peć Patriarchate, reciting the Jesus Prayer with a prayer rope. It took hours. Then I felt the grace descending upon me. Endorphins gushed from my brain. I was no longer afraid of anything. I came across two huge Sharr dogs. They were eating a dead donkey that someone had killed with a car. Whimpering, they let me pass. I threw away the most valuable thing for a journalist—a phone book with three thousand numbers. Not a single stone hurt me. I reached the Patriarchate and, for the first time, truly prayed for all the dead and living I could remember. Nine hundred million people attacked a tiny country with five to six million Serbs. I knew the end was near.

The End

I have written around a thousand stories. I have published thirteen books. My best-written book has just been released by the Serbian Literary Cooperative: Mrtvi dim (Dead Smoke). The second edition of Đavolje jaje (The Devil's Egg) has appeared in Službeni Glasnik bookstores. You won’t find my most important books in bookstores, so if you want to read them, you must contact the author directly by phone at +381 62 80 70 297. And I still wander through Serbian lands, "on the wicked path in search of a story!"